While attempting to investigate an alternative vision of India, director Ravi Jadhav produces a dull story interspersed with eloquent speeches from the politician-poet.

Main Atal Hoon uses large brushstrokes to depict the vibrant personality of Atal Bihari Vajpayee; it is largely a fawning tribute and hardly an assessment. The movie offers a fantastic opportunity to comprehend the kind of foundation that supported the ascent of right-wing politics in India, and it is based on journalist Sarang Darshane’s biography of the former prime minister. Vajpayee, a young poet who grew up by the Yamuna, decides to focus on the suffering endured by the laborers who built the Taj Mahal, an enduring symbol of love. A tea vendor tells a young Vajpayee that he listened to Jawaharlal Nehru’s speech on the day India gained independence, but he was unable to understand a word because it was all in English. Vajpayee became the voice of a different vision of India.

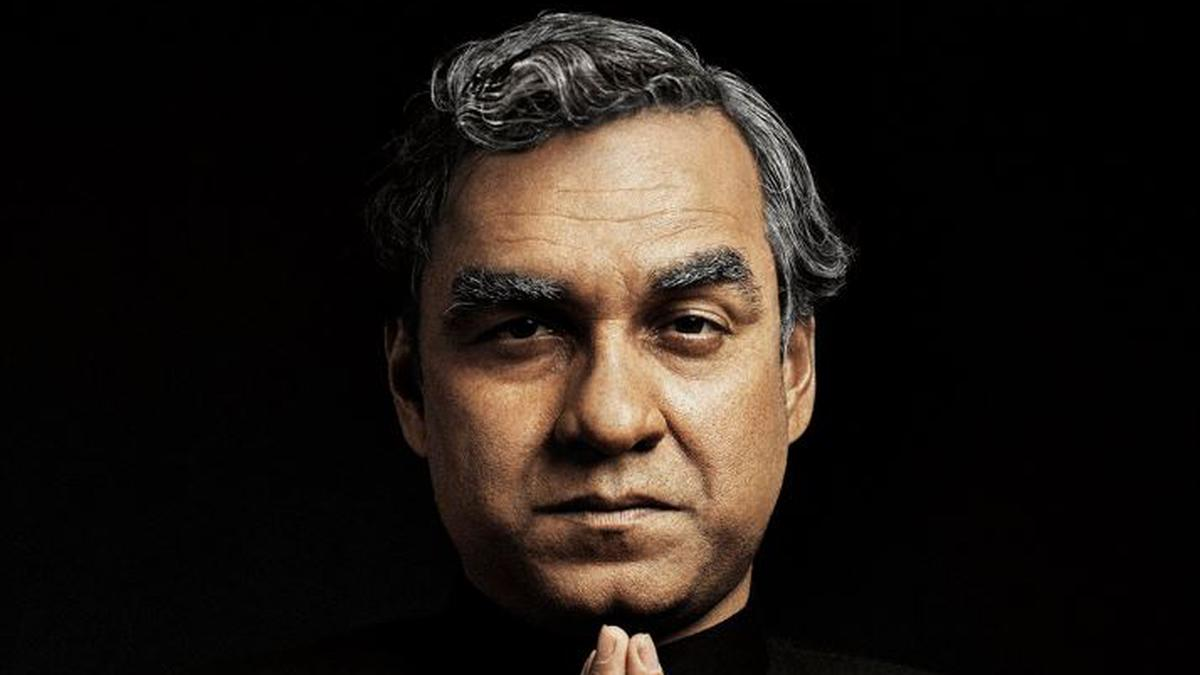

Main Atal Hoon:Pankaj Tripathi

For the most part, it’s still a broad view, tinged with unqualified praise for the popular leader who stated that supporting Hindutva ideology and being a liberal democrat are not mutually exclusive. It barely reveals to us how the conservative mind got started and how his worldview developed. Instead, it decides to be cautious. It is unclear what Vajpayee considered Gandhi. His close friend Sikandar Bakht, his ability to forge friendships with people from different political backgrounds, and the fact that some of his progressive ideals encountered resistance within the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), his parent organisation, are all left out.

Pankaj Tripathi makes a valiant effort to capture the captivating essence of Vajpayee. Similar to the former prime minister, Tripathi is a skilled orator who can captivate an audience. He portrays Vajpayee’s equanimity and calm resolve in the face of a crisis so well that even his detractors have compared him to Teflon-coated. This is in addition to his aging-related changes in mood and demeanor. Strangely, Tripathi hasn’t gained weight to portray an aging Vajpayee, but for the most part, it doesn’t affect how well he performs.

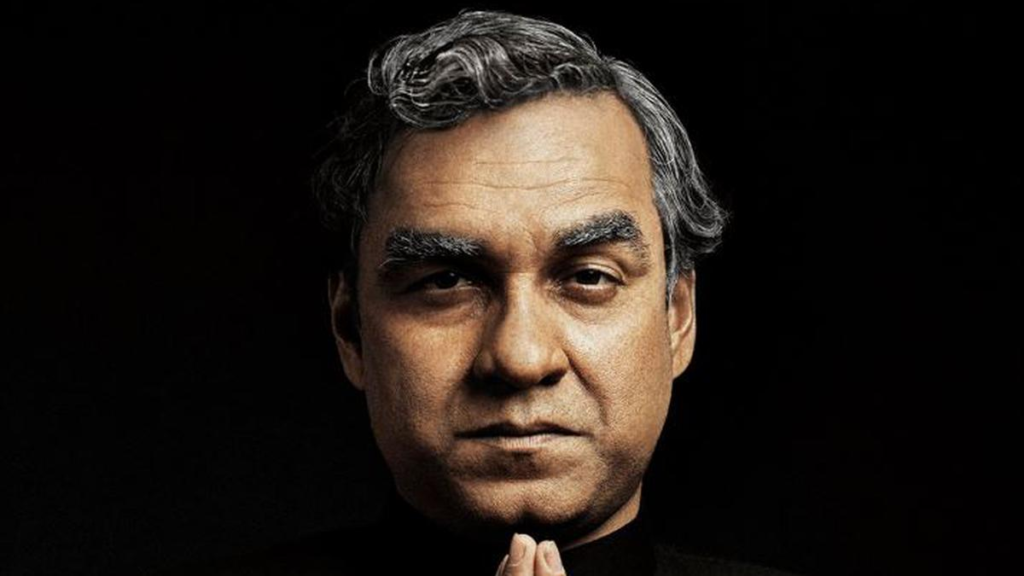

But the actor’s performance is hindered by glib writing that sounds genuine. His cause is further hampered by a production design and sound that lack originality. When it comes to contentious issues, Director Ravi Jadhav rarely sheds the moderate mask that some of his senior colleagues have painted for him. Nor does he look into the doublespeak he has engaged in. The movie discusses the seemingly contradictory opinions of a liberal man in a conservative party twice: In his speech in Lucknow the day before the Babri Mosque was demolished, Vajpayee discusses leveling the surface but also expresses profound regret following the outbreak of communal riots across the nation. Then, Jadhav provides a brief glimpse into the leader’s private life. He is well-known for having called himself a bachelor.

Vajpayee’s penchant for meat and alcohol doesn’t hold up in a time when the mob is also scrutinizing what is prepared and consumed by characters on screen. The film ignores the ways in which his travels abroad influenced the development of his progressive outlook in both his personal and professional lives. More significantly, it denies room to Balraj Madhok and Dattopant Thengadi, two of his opponents and critics in the Jan Sangh and Sangh Parivar. Additionally, it makes no mention of the Mandal Commission report when discussing the Ram Temple Movement.

Main Atal Hoon: Pankaj Tripathi

Raja Sevak’s portrayal of Lal Krishna Advani falls flat, despite Daya Shankar Pandey and Pramod Pathak’s portrayals of Deen Dayal Upadhaya and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee being fairly rendered. Advani’s complicated relationship with his senior and his friend is also not adequately depicted in the writing, especially when he is the movie’s voice actor. He also reduces the second-most significant character in the movie to a caricature. It remains unclear why he elevated Vajpayee from the sidelines to the forefront. The actors portraying Sushma Swaraj, APJ Abdul Kalam, and Pramod Mahajan engage in cheesy imitations of the iconic performers. After the intermission, it appears that Tripathi is acting out scenes from the BJP manifesto in order to cross off Golden, Kargil, Pokhran II, and the Lahore Bus Ride.

Vajpayee’s scathing criticism of the Congress’s anti-democratic practices takes center stage in the story, but his graciousness in recognizing Nehru’s contribution also finds room. It takes us back to a time when there was no barrier between ideologies. The film unintentionally offers some delicious meta moments where Vajpayee, the reputable opposition leader, speaks truth to power, which is why the revision is timely. His venomous remarks following the Emergency, in which he accuses Indira Gandhi of crony capitalism and power arrogance, still seem pertinent today.